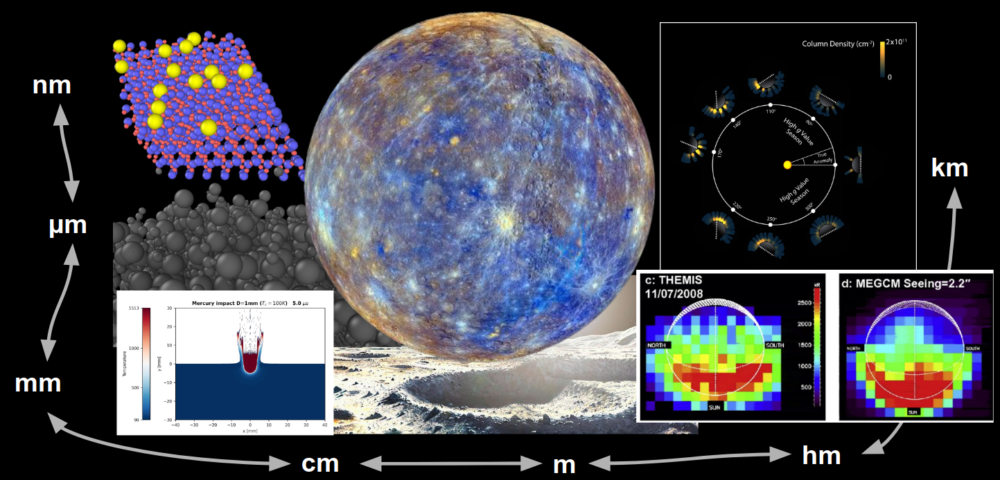

For nearly 40 years, planetary science studies of the exospheres of Mercury, the Moon, and other airless bodies have been hindered because of uncertainties in our understanding of the surface processes influencing exosphere formation. When meteoroids, the solar wind, and photons impinge onto the surfaces of airless bodies in the Solar System, they produce an atmosphere so thin that atmospheric species do not interact with each other, forming a non-collisional exosphere. Although such surface bound exospheres are thought to be the most common class of atmospheres in our Solar System, they remain poorly understood to date. Understanding these exospheres is crucial for understanding the dynamics of volatiles on the moon and other bodies with surface boundary exospheres. It is now recognized that the description of the exosphere- surface interface is a major topical area that requires improvements (Teolis +2023). The accurate description of the gas distribution at exit to vacuum is important because atoms and molecules experience no collisions after their release from the surface in the rarified environments surrounding bodies like Mercury and the Moon. Recent measurements (e.g., LADEE, LRO, MESSENGER) indicate the necessity of considering how gases interact with the uppermost surface on a microphysical scale if we wish to understand macroscopic exospheric processes. For instance, lunar volatiles, which freeze out at night, do not sharply outgas at sunrise (Keggereis +2017; Grava +2023), and it is not understood why this occurs based on available experimental data which indicate that argon should easily desorb at low temperatures. To some extent it has been proposed that the geometric voids between regolith grains can act as an additional stopgap which prolongs the gas residence due to diffusion deeper into regolith, an effect not considered in the majority of exosphere models, which treat the gas-surface interface as a flat boundary (Sarantos and Tsavachidis, 2020;2021).

Other unexplained issues in this broad area of work are a curious cycle of Mercury’s sodium exosphere, with periodic afternoon enhancements ofexospheric sodium which current models cannot explain (Leblanc+ 2022). Finally, it is not understood why all analyses of exospheric helium measurements around the Moon suggest that this species thermally accommodates (e.g., Grava et al. 2021), whereas this noble and light atom is expected to interact very weakly with the surface. In many cases stated above, laboratory experiments are either not available for the specific gas- surface system, or are too complex to interpret when performed with powders such as lunar samples which could have been pacified since brought to Earth. Theoretical calculations are needed to provide the bulk of the data required to provide new insights on how to update the existing treatments of gas interaction with the surfaces of Mercury and the Moon. Modelling has identified key processes thought to be responsible for the presence of a surface bound exosphere: thermal stimulated desorption, photon stimulated desorption, micro-meteoroid impact vaporization and solar wind ion sputtering (Shemansky & Morgan 1991, Leblanc & Johnson 2003, Wurz +2010, Gamborino +2019, Chaufray +2022, Mura +2023). However, once an atom is ejected from the surface it can either escape the object gravity, or it can follow a ballistic trajectory ruled by radiative pressure and gravity, until it eventually falls back on the surface. As it reaches the regolith, it can either bounce or adsorbed chemically or physically. The fate of these returning atoms is often not considered in exosphere models. More recent exosphere studies have investigated the effects of the subsurface diffusion of atoms inside the top first meter of the regolith of these objects (Teolis +2023). However, many of the observed features, such as the cold longitudes sodium enhancement of Mercury measured by MESSENGER, have yet been understood (Cassiny +2016). More recently, BepiColombo data for Mercury exhibited a decrease in the helium density measured by a factor 5-7.5 with respect to Mariner 10 observations (Quémerais +2023). In addition to Mercury, recent observations of the Ganymede exosphere with JWST also showed local enhancement of CO2 in the moon’s exosphere, suggesting a complex gas-surface interaction dependent on the surface composition. This stresses the need for an improvement of the gas-surface interactions in surface-bound exospheres, where a better description of the basic ejection processes sustaining the tenuous atmospheres is needed. Such improvement will allow to better prepare the data interpretation of future mission such as BepiColombo, JUICE, Europa Clipper, or the Artemis missions.

Atomistic Modelling:

These ejection processes all rely on the basic notion that in all cases an emitted atom must overcome the a binding energy with the surface in order to be ejected into the exosphere. For many species, this surface binding energy (SBE) is very poorly constrained. The existing experiments have either derived SBEs energies for monoelemental substrates, not representative of the mineral surfaces found on Moons and planets (Yakshinskyi +2000), or are too complex to interpret the gas-surface interactions correctly when using sample or analogs powders. Instead, a focus of this team will be on using molecular dynamics (MD) simulations to study gas-surface interactions directly on the atomistic scale. MD simulations work by iterating positions and velocities in a system using an interatomic potential that defines the forces between the interacting particles. Because all interactions are captured in the simulation, MD removes the assumption of binary collisions and can be used to simulate both amorphous and crystalline samples. Furthermore, unlike common sputtering binary colliasion a approaches, SBE is not a user input but is instead a function of the atomistic interactions on the surface of the substrate. The proposed team possesses expertise in developing MD simulations of irradiation and in studying surface energies from different mineral surfaces. Therefore, the necessary interatomic potentials and intial scripts have already been developed. We will work together to make this models more representative of realistic surfaces, capturing the role of bonding states, surface coverage, and surface diffusion. We will also investigate using novel potentials that employ machine learning algoritms to improve predictions. Outputs from MD models such as SBEs and diffusion coefficients will then be incorporated into granular and exosphere models to model surface-boundary exospheres with higher fidelity. These results will inform, and can be adopted by all community models in this broad area of work.

References

- Cassidy, T. A., McClintock, W. E., Killen, R. M., Sarantos, M., Merkel, A. W., Vervack Jr, R. J., & Burger, M. H. (2016). A cold‐pole enhancement in Mercury’s sodium exosphere. Geophysical research letters, 43(21), 11-121.

- Chaufray, J. Y., Leblanc, F., Werner, A. I. E., Modolo, R., & Aizawa, S. (2022). Seasonal variations of Mg and Ca in the exosphere of Mercury. Icarus, 384, 115081.Gamborino, D., Vorburger, A., and Wurz, P. (2019). Mercury’s subsolar sodium exosphere: an ab initio calculation to interpret MASCS/UVVS observations from MESSENGER, Ann. Geophys., 37, 455–470, https://doi.org/10.5194/angeo-37-455-2019.

- Grava, C., Hurley, D. M., Feldman, P. D., Retherford, K. D., Greathouse, T. K., Pryor, W. R., … & Stern, S. A. (2021). LRO/LAMP observations of the lunar helium exosphere: constraints on thermal accommodation and outgassing rate. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 501(3), 4438-4451.

- Grava, C., Killen, R. M., Benna, M., Berezhnoy, A. A., Halekas, J. S., Leblanc, F., Nishino M. N., et al. (2021). Volatiles and Refractories in Surface-Bounded Exospheres in the Inner Solar System. Space Sci Rev 217, 61 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11214-021-00833-8

- Kegerreis, J. A., Eke, V. R., Massey, R. J., Beaumont, S. K., Elphic, R. C., & Teodoro, L. F. (2017). Evidence for a localized source of the argon in the lunar exosphere. Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets, 122(10), 2163-2181.

- Leblanc F., Johnson R.E., Mercury’s sodium exosphere, Icarus,Volume 164, Issue 2, 2003, Pages 261-281, ISSN 0019-1035, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0019-1035(03)00147-7.

- Mura A., Plainaki C., Milillo A., Mangano V., Alberti T., Massetti S., Orsini S., Moroni M., De Angelis E., Rispoli R., Sordini R., The yearly variability of the sodium exosphere of Mercury: A toy model, Icarus, Volume 394, 2023, 115441, ISSN 0019-1035, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.icarus.2023.115441.

- Quémerais, E., Koutroumpa, D., Lallement, R., Sandel, B. R., Robidel, R., Chaufray, J. Y., … & Corso, A. J. (2023). Observation of Helium in Mercury’s Exosphere by PHEBUS on Bepi‐Colombo. Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets, e2023JE007743.

- Sarantos, M., & Tsavachidis, S. (2020). The boundary of alkali surface boundary exospheres of Mercury and the Moon. Geophysical Research Letters, 47(16), e2020GL088930.

- Sarantos, M., & Tsavachidis, S. (2021). Lags in desorption of lunar volatiles. The Astrophysical Journal Letters, 919(2), L14.

- Shemansky D. E., Morgan, T. H., (1991). Source processes for the alkali metals in the atmosphere of Mercury, Geophysical Research Letters, Volume 18, Issue 9, https://doi.org/10.1029/91GL02000

- Teolis, B., Sarantos, M., Schorghofer, N., Jones, B., Grava, C., Mura, A., … & Galluzzi, V. (2023). Surface Exospheric Interactions. Space Science Reviews, 219(1), 4.

- Wurz, P., Whitby, J. A., Rohner, U., Martín-Fernández, J. A., Lammer, H., & Kolb, C. (2010). Self-consistent modelling of Mercury’s exosphere by sputtering, micro-meteorite impact and photon-stimulated desorption. Planetary and Space Science, 58(12), 1599-1616.

- Yakshinskiy B. V., Madey T. E., Agreev V. N. (2000). Thermal Desoption of Sodium Atoms from Thin SiO2 Films. Surface Review and Letters, 7, 75–87. doi: 10.1142/S0218625X00000117